3 NOVEMBER — A PERSONAL RETELLING

A personal recollection of the 1988 coup — and how it became a story I had to tell.

It started with a bang.

I was still half asleep in Colombo when my Sri Lankan landlady burst into my room and shouted,

“Maldives has been attacked!”

For a moment, I thought I was dreaming. But her voice had that tremor people get when the world suddenly tilts.

Back then, social media wasn’t even a dream, and the internet was just a rumor from another planet. Communication was fragile and expensive — one cut cable, one dead line, and a nation could vanish into silence.

That morning, the telephone lines to the Maldives went dead. Every few minutes, I twisted the dial on my FM radio, trying to catch Voice of Maldives — the station where my mother was an anchor.

Normally, even through weak signals, I could recognize the rhythm of home: the calm, familiar tone of the announcers — especially hers — and a song fading gently in and out.

But that day, there was only static. A haunting, endless static.

It felt like the country itself had been swallowed by it. That feeling — helplessness mixed with fear — stayed with me.

Fourteen years later, in 2002, I turned that memory into a story.

Representing the Ministry of Atolls Administration, I wrote and directed a TV drama for the TVM Office Teledrama Competition.

But I didn’t want to tell the story from the frontlines of Malé. I wanted to tell it from the edges — from a remote island where the only connection to the world was rumor and radio.

The story followed Arif (Ali Waheed), a banished drug addict from Malé, serving his term in that island. Beneath his rebellion and defiance lay a lifetime of unresolved pain — an unhealed wound from his father, Sattar (Mohamed Asif).

When the coup unfolds, and communication with Malé is cut off, Arif’s fear for his estranged father becomes the story’s emotional heartbeat. The thought that something might have happened to the man he both hated and missed forces him to confront what he’s been running from all along.

The drama opened the same way that morning had begun for me — Jameel (the late Mohamed Saleem), Arif’s caretaker, twisting the radio dial, searching for a voice in the static.

As Jameel, Arif, and their co-workers debated over the silent radio, someone ran through the forest shouting,

“Malé has been taken over!”

The island erupted in fear.

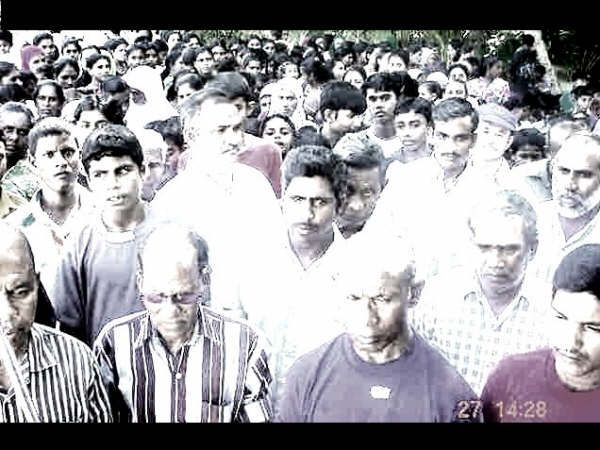

That scene was the most logistically challenging I’ve ever shot. My cinematographer, Abdul Latheef, and I spent a week planning every frame — the crane shots, crowd movements, and pure, unfiltered chaos.

We shot on a Friday, when most islanders were home. We started wide and ended close, knowing our extras’ patience would fade before our energy did. By the time we wrapped, half the crowd had gone home — but the emotion stayed raw and real.

It remains one of my favorite sequences I’ve ever directed.

And I didn’t create it alone.

The late Mohamed Saleem was my compass. He wasn’t just an actor — he was part of that history. On the day of the coup, he was serving in the NSS (now MNDF) and had been taken captive by the mercenaries.

His firsthand memories shaped the script. He helped me understand the fear, the sound, the silence.

When Saleem looked at that radio, he wasn’t acting — he was remembering.

Before filming, I studied every account I could find. But what truly shaped the drama was a three-hour home video my brother-in-law had filmed in Malé during the coup.

He recorded everything — crowds, panic, prayers, and the pulse of a nation on edge. That tape became my time machine.

Later in the story, Arif rushes to a group of islanders gathered around a radio. He tunes until he catches a faint Voice of America broadcast. The crowd leans in as he translates:

“The capital is under attack. The President and his cabinet have been captured.”

That moment wasn’t fiction — it used real audio from that same tape. Every crackle of static, every tremble in the voice, untouched.

From that tape, I also recreated scenes of panic — islanders queuing at shops, buying rice and tinned food, preparing for an uncertain tomorrow.

The next morning, in real life, I was still in Colombo when the radio came alive again.

And then I heard it.

My mother’s voice.

Through that fragile frequency, she announced that the mercenaries had fled — that the country was safe. Her voice trembled with exhaustion and relief.

I’ll never forget that sound.

In the drama, Arif wakes to the same moment. The radio hums softly with a Qur’an recitation, the same surah that played before my mother’s real-life announcement. Then — the words of salvation.

What followed was a montage of joy — children running, flags raised, laughter through tears. My small tribute to the kind of humanity Michael Bay often captures after chaos.

But one voice was still missing.

I wanted to include the President’s full post-victory speech — the one broadcast right after calm returned. Finding it became a mission.

I searched archives, old offices, and friends — until my brother-in-law’s brother found a copy.

At first, I planned to use only a few seconds. But during post-production, I realized it wasn’t just a speech. It was the sound of a nation breathing again.

I used the entire address, layering it over visuals of people listening on radios — at communal spots, verandahs, and corners. Faces in awe. Faces in prayer. Faces in gratitude.

In the final scene, a worried Arif, unable to contact his family, watches locals playing football. Jameel calls out to him.

“Arif!”

Arif turns.

Jameel and his friends step aside.

And there — in the center of the frame — stands Sattar, his father.

No dialogue. No explanation.

Just two men — broken, and finally whole.

It remains one of the most honest endings I’ve ever filmed.

The drama went on to win Best Director, and on most 3rd Novembers, TVM re-runs it.

For me, 3rd November is not just a celebration of triumph. It’s the sound of static turning into a heartbeat. It’s Saleem’s trembling hands on a radio dial. It’s the voice of a mother breaking through fear. It’s the moment a nation — terrified, disconnected, but unbroken — found its voice again.

Because sometimes, history doesn’t begin with silence. It begins with a bang.